The case against rubrics

“Why don’t you give students rubrics when they provide peer feedback in Short Answer?” It’s a question we hear often from teachers and administrators. Answering it requires a quick review of learning research. Inspired by the work of Dr. Greg Ashman (2015) and the analysis of Dr. Dylan Wiliam, the images below help illustrate our explanation.

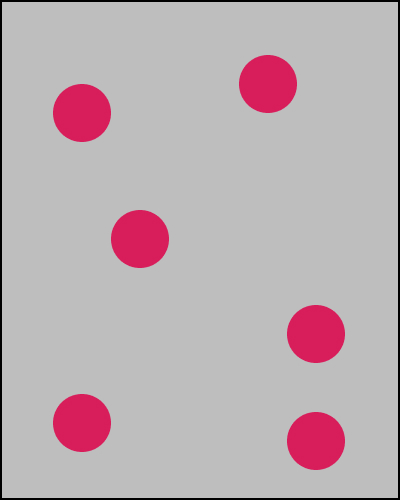

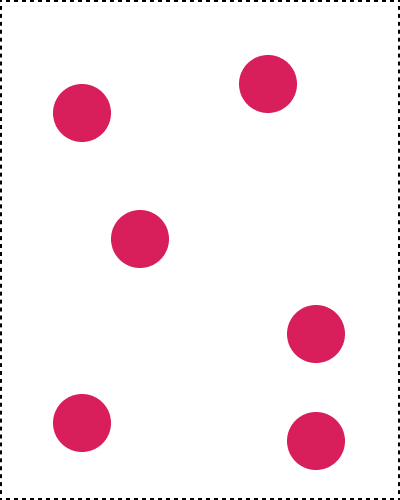

1. Ideal performance on a given writing task

2. Key features of ideal performance highlighted for a rubric

3. Learners using the rubric to reproduce only the highlighted features

Rubrics are helpful for students because they identify important aspects of quality and make assessment feel less arbitrary. But, as the images above illustrate, rubrics also tend to highlight only the key features of ideal performance. In the process, they often leave out other important qualities, especially when it comes to writing. They can also lead students to focus so much on the individual “parts” of writing that students sometimes forget that great writing is, instead, the sum of the parts. And where rubrics have been shown to improve student performance (i.e. how well students do on a given task), the research is a bit more mixed on whether or not they promote real learning (i.e. a change in a student’s long term memory). See p.71-81 in Dr. Dylan Wiliam’s Embedded Formative Assessment for a more detailed explanation.

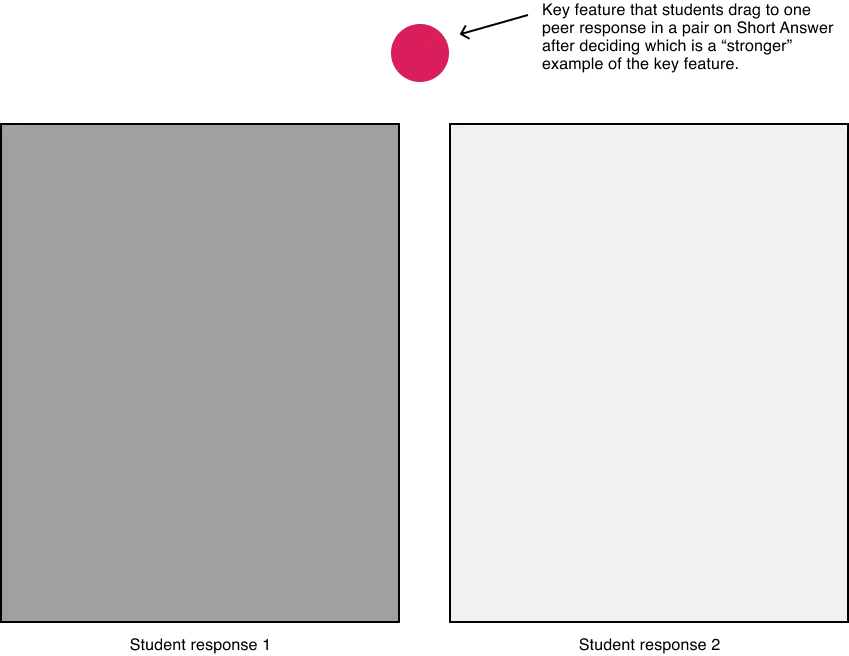

The case for comparative judgment

We believe comparative judgment (CJ) to be a better way to develop student writing ability. There are several reasons for this, but chief among them is that students must construct on their own what makes for quality writing. Key features of quality are still identified for them as a scaffold (the red dot above), but they aren’t given descriptions of these key features. Instead, they form these descriptions on their own by reading multiple peer exemplars and awarding points through the process of comparison. We believe this is a better way to get students to consider “the sum of the parts” of quality writing. In doing so, we believe students are more likely to develop the tacit knowledge necessary to become better writers. Hearing “I know what I need to fix now that I read my peers response” from students gives us confidence that we’re facilitating these learning outcomes with Short Answer.

For more on the learning research guiding Short Answer, check out our research base and theory of change below. If you’d like to discuss this in more detail, feel free to schedule a call with our team anytime.