Designed at the Stanford Graduate School of Education

The Short Answer Approach

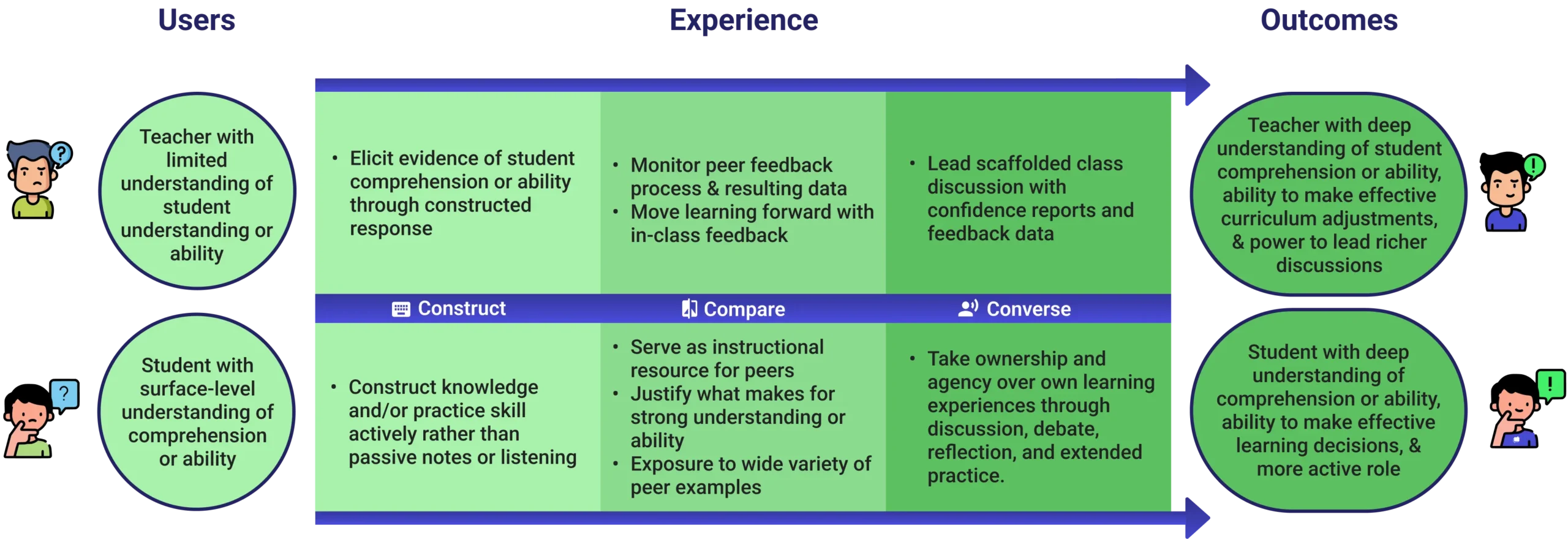

Short Answer is grounded in research based best practice in formative assessment and writing instruction. Our theory of change below explains how teachers and students can use Short Answer to improve learning outcomes. This theory guides the development of Short Answer. You can read more about it below and check out our efforts to study this theory in our efficacy portfolio.

An Experience Built on Learning Science

Short Answer’s approach has been approved by faculty in Stanford’s Learning Design & Technology program, the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, and learning science researchers in the 2021 Futures Forum on Learning Tools Competition.

Formative Assessment

Eliciting student understanding to adjust instruction is one of the most effective teaching strategies that improves student achievement. Short Answer amplifies teachers’ ability to elicit student understanding by actualizing the five key strategies of formative assessment identified by Black & Wiliam (2009) in their seminal study1,2:

1. Clarifying and sharing learning intentions and criteria for success

Teachers easily monitor student responses and lead discussions to create a shared understanding

2. Engineering effective classroom discussions & other learning tasks that elicit evidence of student understanding

Discussion and debate of peer-constructed responses are central to all Short Answer activities

3. Providing feedback that moves learners forward

Every student receives immediate, actionable feedback through direct comments and class discussion

4. Activating students as instructional resources for one another

Students learn by both receiving and giving feedback to others

5. Activating students as the owners of their own learning

Self-rated confidence scores before and after Short Answer activities enable students to reflect on their own comprehension and calibrate their learning.

Comparative Judgment

A nascent body of research suggests that comparative judgment (CJ), the process of choosing one option within a series of pairs, is a “powerful tool for improving formative assessment pedagogical practices.”3 Studies using CJ used for formative assessment resulted in improved learning outcomes for students.4 In one study, 89% of middle school students reported implementing changes to their work based on the peer feedback provided as a result of CJ, showing that this process drives students to take an active role in their learning.3 CJ activates peers as instructional resources for one another, supporting the effective formative assessment framework cited above.

Activating Students as Instructional Resources for One Another

Short Answer’s motivating and engaging peer-driven activities improve student learning at four stages: creating responses, giving feedback, receiving feedback, and discussing feedback. A wide array of research describes the positive impacts of peer feedback on student learning, especially when completed with adaptive comparative judgment:

- Students’ comparison-based ranking of work matches that of the expert instructor.4

Students feel motivated to talk about evaluations of peer work because the experience of evaluation is enjoyable.5

Peer feedback can lead to students making more revisions on their work.6

Frequently participating in peer feedback activities improves performance on assessments.7

Teachers can trust the feedback done by their students and know that all students, regardless of prior experience or content knowledge, can thrive in the Short Answer peer feedback process. Feedback is present in every part of life, and Short Answer strengthens students’ collaboration, support, and empathy skills. With Short Answer, teachers can instill a positive culture of feedback – that it is something to welcome, not run away from – early on in a student’s life.

Active, Social Learning

Our founding team has long believed that Active Learning > Passive Learning. Instead of the passive “sit-and-get” experience of taking notes on a lecture, Short Answer’s interactive and highly social activities get every student actively engaged in the classroom.

Learners show an increased level of effort in the presence of others.8 Students will be more motivated to construct responses to the best of their ability when they know peers are going to see and discuss their answers. The emphasis on viewing student-constructed work in a peer audience engages students while pushing them to put forth their best effort.

Feedback that moves learning forward

Learners need feedback in order to improve their understanding. Even more, that feedback needs to be immediate rather than delayed in order for students to care about, internalize, and implement it. Short Answer leverages the power of numbers – peers! – to ensure that all students get actionable feedback that moves their learning forward in class. Short Answer’s feedback approach is grounded in the research of Dylan Wiliam (2011) in that it:

- Dedicates class time for students to think about and use feedback

- Offers specific suggestions for improvement rather than what was done wrong

- Encourages discussion of what makes for strong understanding of material

Knowledge Construction

There’s a difference between what a student knows and what a student can do with what they know. Our approach enables insight into the latter. Bloom’s Taxonomy (2021) suggests that the construction of knowledge elicits higher-order thinking and, subsequently, a more meaningful reflection of learning when compared to the recognition-level retrieval tasks that most digital tools rely on.9 When students retrieve and construct knowledge, they’re also less likely to experience the “illusions of competence” that result from formative assessments that rely on recognition of knowledge, thereby improving the metacognitive ability to monitor their own understanding.10 Short Answer enables students to actually show what they can do and gives teachers deep insight into their students’ comprehension, creating a richer, more meaningful formative assessment experience for all.

Citations

1. Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability (formerly: Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education), 21(1), 5-31.

2. Wiliam, D (2011). Embedded Formative Assessment

3. Bartholomew, S., Strimel, G., & Yoshikawa, E. (2019). Using adaptive comparative judgment for student formative feedback and learning during a middle school design project. International Journal of Technology & Design Education, 29, 363-385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-018-9442-7

4. Jones, I & Alcock, L. (2014). Peer assessment without assessment criteria. Studies in Higher Education, 39(10). 10.1080/03075079.2013.821974

5. Jones, I., & Wheadon, C. (2015). Peer assessment using comparative and absolute judgement. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 47, 93-101.

6. Cho, K., & Schunn, C. D. (2007). Scaffolded writing and rewriting in the discipline: A web-based reciprocal peer review system. Computers & Education, 48(3), 409-426. DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2005.02.00

7. Jhangiani, R. S. (2016). The impact of participating in a peer assessment activity on subsequent academic performance. Teaching of Psychology, 43(3), 180-186.

9. Anderson, L.W. (Ed.), Krathwohl, D.R. (Ed.), Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M.C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Complete edition). New York: Longman.

10. Karpicke, J. D., Butler, A. C., & Roediger III, H. L. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student learning: do students practise retrieval when they study on their own?. Memory, 17(4), 471-479