When we lead professional development with schools at Short Answer, we often open with a controversial statement: Peer-to-peer feedback can be just as effective as feedback provided by teachers. This is true *IF* the peer feedback is scaffolded correctly. For us, that means using comparative judgment.

Comparative judgment

The “Law of Comparative Judgment” was conceived in 1927 by psychologist Louis Thurstone. It was generated as an assessment approach to assign more consistent scores to perceived concepts, as psychologists were persistently struggling to get individuals to consistently assign the same value to similar work. To illustrate this point, answer the following: “Is the purple square above this paragraph dark?” If we asked this question to 10 people, we might get 10 different responses.

To combat this phenomenon and produce more reliable measurement, Thurstone proposed a move away from individual value-judgments. Instead, individuals should work through a series of comparisons in which they identify the ‘better’ of two items. Thurstone, along with a growing body of researchers since, has shown that this method is an effective way to get more reliable measurement of psychological phenomena (Pollitt and Murray 1996; Pollitt and Whitehouse 2012; Pollitt 2015). To illustrate this point, answer the following: “Of the two purple squares below this paragraph, which one is darker?”

Comparative judgment in education

Only recently has the concept of comparative judgment been tested as a means to more reliable assessment in K12 education (Davies et al. 2012; McMahon and Jones 2015; Steedle and Ferrara 2016; Christodoulou 2017). In 2019, researcher Scott Bartholomew at BYU was one of the first to study comparative judgment as a scaffold for peer feedback. The results of his work were one of the original motivating factors for our team to create Short Answer.

87% of students in Bartholomew’s study reported that providing and receiving feedback via comparative judgment helped their learning. 89% of students reported making changes to their work based on the feedback provided from peers. Remarkably, the feedback and rank order created by the students via the comparative judgment process aligned very closely with the order and scores produced by teachers using traditional rubrics. Put another way: By scaffolding peer feedback through the medium of comparison, students were able to provide feedback at the same quality and reliability as their teachers.

Comparative judgment in Short Answer

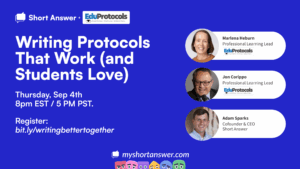

Bartholomew’s research is at the heart of Short Answer’s approach. By scaffolding peer feedback via comparative judgment, Short Answer empowers teachers to activate students as reliable instructional resources for each other. This reduces the overall feedback workload for teachers, especially when it comes to writing practice, empowering teachers to increase the amount of writing practice happening in their classrooms without increasing their workload. In our view, increased writing practice + increased high quality feedback = much stronger K12 writers. In the process, we create an environment whereby students learn by both giving and receiving feedback.

Want to learn more? Check out our video explanation above. Better yet, try this all out in your classroom for free at www.myshortanswer.com.