I (Adam Sparks, cofounder of Short Answer) have felt something like a nerdy version of a touring rock band lately. I’ve been “on tour” sharing Short Answer and working with teachers on adjusting writing instruction and assessment in the wake of AI at 6 different Edtech conferences over the last three months. After hearing dozens of keynotes and breakout sessions, I started noticing trends. Here are 6, along with what I think they mean for schools.

1. AI! AI! AI! …. AI?

AI dominated the narrative at every conference: Keynotes, breakout sessions, conversations in the hallways…everywhere someone was talking, “AI” was being muttered. That said, there was a noticeable difference in tone compared to even 6-8 months ago.

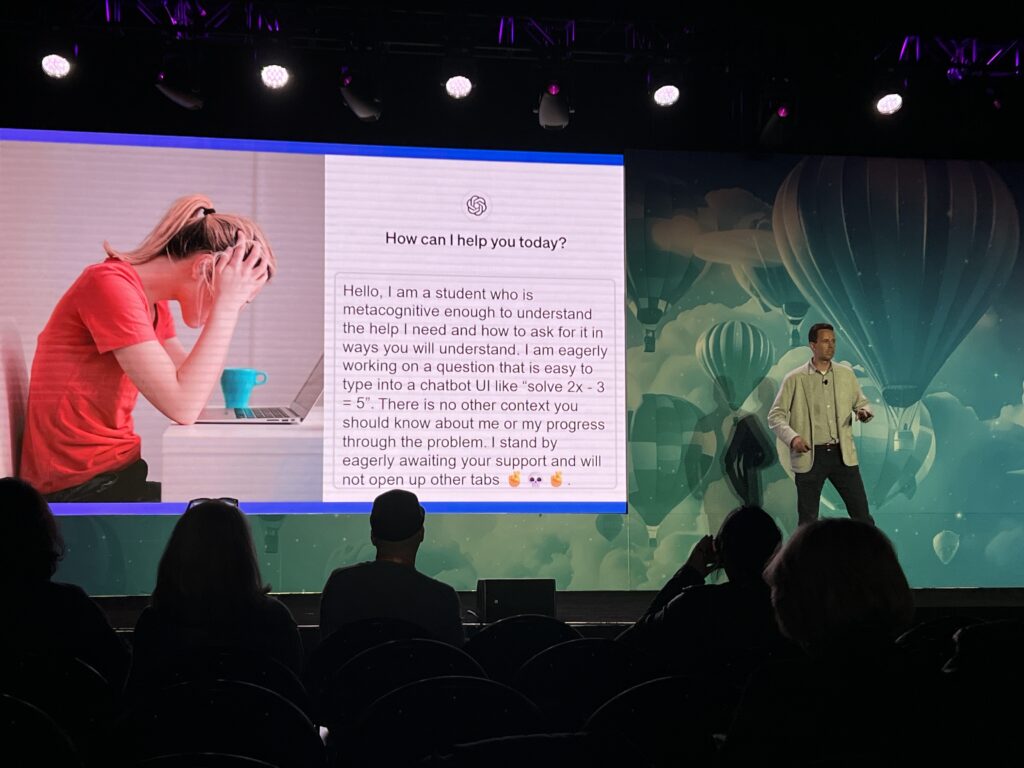

The novelty of AI is beginning to wear off. Teachers and school leaders are beginning to ask harder questions about efficacy, data privacy, over reliance, and what AI can and can’t do when it comes to instruction and assessment. This skepticism was put into relief most dramatically in Dan Meyers’ scorched-earth keynote at the AIR Show in which he called out the “fantasies of tech and business leaders” literally IN THE VENDOR HALL within eye and ear shot of the booths of said tech and business leaders. I would recommend watching the recording here and you can read more about Dan’s skepticism towards AI here. A key part of his argument is that high quality teaching is about relationships; it’s about the learner just as much as the learning. As Dan argues, AI struggles with this concept.

What it means for schools

You can and should use AI in your classroom. But the dynamic needs to be AI in the loop, teacher in charge. That dynamic is the core message of the workshops we’ve led this spring. If and when grading or lesson planning or IEP updates or etc. etc. etc. are entirely outsourced to AI, we run the risk of our classrooms turning into Teacher in the loop, AI in charge. This dehumanizes education and risks damaging one of the most important factors in student learning: The relationship students have with their teacher.

2. So. Many. AI. Tools.

It’s official: There are too many new AI tools. I feel comfortable saying as much after attending the AI AIR Show in San Diego in which well over 50 of the now 320 (and counting!!!) new AI edtech companies exhibited or presented. As edtech business analyst Ben Kornell wrote afterwords, “the Cambrian explosion of AI in Edtech is entering a Darwinian moment….the AIR Show made it clear that the company to customer ratio is just not equal right now.” Put another way, many of the new AI tools that exist today likely won’t all be standing a few years from now. There just aren’t enough customers and there’s too much overlap in services.

What it means for schools

The evergreen advice holds: Be intentional when integrating new edtech tools into your practice, especially when it comes to purchasing. It is highly likely that many of the “free” AI tools you may be using now will soon be paid….and when that happens and folks don’t pay, many of the new AI tools will either merge with other platforms or go out of business. Speaking of which…

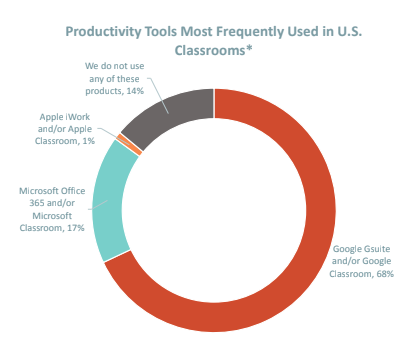

3. The tortoises may soon overtake the hares

I had a spontaneous lunch with a product lead at Microsoft education during ASU/GSV. At one point, when discussing the neighboring AI AIR Show and the hundreds of tools represented, this individual said something like, “You know, there’s a lot of cool stuff over there. But it does feel like many companies are doing largely the same thing. And none of it feels defensible.” The “none of it feels defensible” line was memorable, especially after attending sessions and talking with folks from Microsoft, Google, Canva, Grammarly, and others. All are currently working on what will, undoubtedly, become landmark AI features within their ecosystems – ecosystems embedded and used daily by almost 90% of schools. And when they do, what does that mean for the 3rd party tools that have stood up in their absence?

Based on some of the conversations I had, the big dogs will be rolling out their AI features sooner rather than later. And when they do, it will have major consequences for the upstart 3rd party tools that have become household names in edtech over the past two years.

What it means for schools

Definitely continue to use 3rd party AI apps. Many of them are doing incredible things that will save you hours of administrative work and enable you to better differentiate instruction . But…maybe hold off on multi-year contracts. There’s a good chance that the workspace you work in everyday will have killer AI features sooner rather than later.

4. Code-red for K12 writing instruction

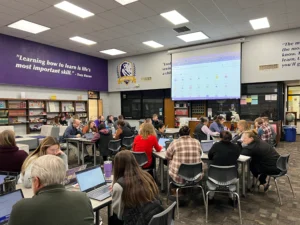

I titled my session this spring “A bot and a hard place: Writing in the Age of AI.” I presented at MACE, NETA, and TCEA. The lines out the door were jarring. The debate over AI detection software, AI feedback, AI essay grading, and what it all means for assessment seems to have completely distracted us from an arguably more pertinent question: What does AI mean for writing instruction? What became clear in talking with teachers in my sessions is that there is a real, urgent need in adjusting writing instruction in the wake of AI.

What should teachers teach? How should they teach it? Why teach it if machines can write 1000X faster and better than many of our students? Teachers don’t just need new tools here – they need clear, step by step, research backed guidance on how to go about adjusting pedagogy to address the challenges and opportunities presented by AI in the writing space.

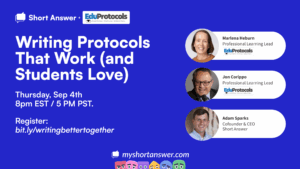

Given the demand and positive feedback, we’ve begun offering our workshops directly to schools and districts. We’ve also started to build many of the concepts we discuss in our workshop into Short Answer so that we can offer them, at scale, to educators everywhere. This requires a lot of building. It’s going to be a busy summer for our team. But we can’t wait to share what we’re working on.

What it means for schools

It’s hard to summarize in a paragraph something we spend hours working through in a half day workshop, but to start, it means rethinking classroom policies and procedures around writing instruction. A simple Red, Yellow, Green system is a good place to start when thinking through your syllabus for next year. Now, speaking of our workshops….

5. Are “AI for EDU Experts” real?

In line with some of the skepticism discussed above, many folks are beginning to question the concept of an “AI in Education Expert” in general. On my LinkedIn, in Facebook communities, on Twitter. Everywhere I looked, I heard the experts I was learning from at many of the conferences I attended were, in fact, not experts. I think this is (well intentioned) nonsense.

I agree with their sentiment, in some sense, in that AI in education is so new that very few can be an true “expert”. Skeptics are right that there is limited research to lean on. They’re also right that many “experts” have no technical understanding of natural language processing, machine learning, or the other underlying technical processes driving LLMs. But here’s the thing, you don’t have to understand the underlying technology to be an expert in it’s application. You can be an expert car driver without being able to explain how combustion engines work. You can be an expert in the application of web-based learning apps without being able to code in JavaScript. And just because we don’t have a lot of peer reviewed research on AI in EDU doesn’t mean we should sit on our hands and wait until we do. There are mountains of precedence to guide us.

After all, AI (at least in our context) is a digital learning tool. Digital learning tools have been around for a long time. The practices these tools facilitate have been around even longer. So if you’re an expert in those practices (i.e. learning science) and in digital learning tools and technology integration, you are more than qualified to speak about AI in education. Suggesting otherwise creates unnecessary drama and does a disservice to educators who desperately need guidance on adjusting teaching and learning in the wake of AI.

And even if we define an “AI in EDU Expert” by the ridiculously high standard of someone who understands the technology behind AI AND how it applies in educational contexts: Those folks exist. Here’s a playlist of them explaining how they feel about AI in education. Spoiler alert- it falls in line with much of the advice I heard from other experts (who don’t have a background in NLP or ML) at conferences this spring.

What it means for schools

Be skeptical of “AI In Education Experts”….but don’t be too skeptical. Rudyard Kipling’s If poem comes to mind. Many of these folks not only know what they’re talking about, they have fantastic guidance and tools that can improve your practice and make your teaching life easier. Skepticism is healthy. But arguing with each other over the definition of expertise distracts us from what should be our focus: Doubling down on research-based best practices in K12 education and finding ways to bend AI towards scaling those practices.

Look for folks that lead with established research, acknowledging that research on AI’s application in education is limited (though my incredible wife and cofounder at Short Answer is actually facilitating some of this research now). For example, we use the long established gradual release or responsibility framework in our workshops when working with teachers on how to introduce AI to students.

6. Yaaaay varied session lengths! Boooo 40 minutes!

TCEA, I’m in love. It was my first time attending Texas’ big edtech conference and I was totally impressed. It had the feel of a national conference, but was small enough to still feel personal. Of all the things TCEA did right, my favorite was varied session lengths: 1 hour, 1.5 hours, 3 hours, you name it. It allowed for depth, which is much needed when wrestling with the existential questions posed by AI, covid learning loss, etc.

It also put into relief just how rushed a 40 minute session is. When sessions are that short, they lead to rushed presenters and the sort of “10 new tools for engagement!” types of presentations that are just too thin to be meaningful. These presentations aren’t necessarily bad, they’re just incomplete. There isn’t enough time to discuss learning research, efficacy, and the nitty gritty of implementation necessary for new tool adoption to be meaningful. Instead, I found myself bombarded by the what and the how.

What I loved about TCEA is that I found myself hearing the why in sessions more often – the research, the background, the context, the nitty gritty. Especially as we continue to be bombarded with new AI tools, the why needs to be our first and most important question. Longer sessions lend themselves to this sort of focus.

What it means for schools

If and when you attend sessions at conferences or adopt new tools, seek out the why. Look for presentations that include research and directly address problems. And, if you happen to be a conference organizer reading this post, please consider offering longer session lengths. Ask the folks at TCEA – longer sessions rock!

Questions? Comments? Concerns?

Please follow up, I’d love to chat more about any and all of this! Click the link below to setup time to chat using my Calendly. Otherwise, keep an eye out for us, because “the tour” continues! If you’re in Texas, we’ll be presenting at the following events soon: